With the alarm set for 7:40am, I went to sleep with the anticipation of tomorrow’s adventure. All

prepared the next morning, I awaited pick up by my personal chauffeur (he never wears a suit and tie?). We set off to pick up someone else in a nearby town. In passing along the roads to Avebury, taking in the scenery of deep rural Wiltshire, there is always time to contemplate life’s important things. Like, how will the day’s challenges go? What are my goals in life? Where do I want to be this time next year? When will spring arrive? Did I turn the grill off and lock the front door!? (We’ve come too far too turn back now!).

The weather man had forecast wintry showers for today and on arrival there was a keen chill to the wind. On passing the barn gallery, I could not miss the looming storm clouds brewing up from the north. Was that rain clouds or snow clouds I wondered, as I headed inside?

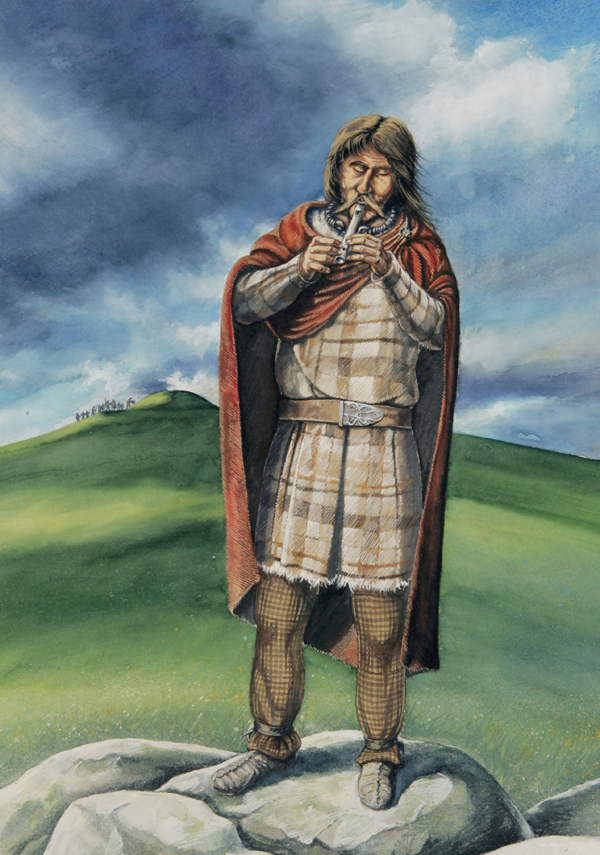

Today in the Ed. room, archaeologist Dr Sara Lunt, Assistant Archaeologist at Avebury Briony Clifton & voice practitioner Yvette Staelens got down to talking about many topics with a central theme around stone. We talked about the sarsen stones that are very numerous in this area and there significance to prehistoric man. We also talked about prehistoric axe heads, with an example passed around for us to examine. This axe head example had been reworked then discarded during the rework. It was a heavy, polished stone with an obvious cutting edge.

During the Neolithic period, agriculture and improved settlement created time and need for

specialisation of tools. These tools were used for cutting wood and clearing ground, for skinning, scraping, butchering and for protection. A high level of workmanship went into making the utility tools. Tools were discarded if impurities or weaknesses were discovered. Axe heads could be made from hard stone and flint which would be chipped, (called knapping) flaking pieces from the main body to create a sharp edge. These tools were often traded or passed within families, generation to generation.

This topic led onto the mention of the ‘Polissoirs’ or polishers. Polissoirs are hard stones that were used to shape and polish flint & stone tools, for example the flint axe heads. Within the Avebury area, sarsen stone was used due to its hard abrasive nature. There are some good examples of Polissoirs to be found locally. Some Polissoirs were later incorporated into the building of the monuments themselves. The stones are generally large and flat, with highly polished indentations being seen running across then. An example of a polissoir made by a student was shown and the smooth surface was very obvious to the touch.

The Preseli Bluestone was also mentioned and passed around. The bluestone comes from

Pembrokeshire, Wales and was used in the construction of some of the inner sections at

Stonehenge. Being igneous in form, the bluestone can be traced back to a precise origin. This

bluestone contains spotted dolerite, local to these Welsh hills. We talked about the movement of this stone and how that may have happened. It was nice to see people discussing the subject

matters with a real honest passion. A level of passion I could relate too with my core interests.

…Then all of a sudden and in answer to my earlier thought, outside it had started to snow!

Eventually turning into proper thick snowflakes too! With the inner child in me brimming, I wanted to go outside and run about in it. I believe at least one other person in the room was feeling the same thing too – (You know who you are). After some more informative talks we headed out to see some sarsen stones in situ. The snow had now stopped but the wind chill was still felt.

We arrived in the picturesque village of Lockeridge to explore the sarsen stones of this area. We

entered Lockeridge Dene by the gate at the front of the site, stopping to read the info board.

We passed many examples of sarsen stones, the whole valley was speckled with them. After a

short time, the sun started to emerge out of the snow clouds, creating a good opportunity for

photographing the stones. As we walked along we listened to talks given about this site from

National Trust Ranger, Peter Oliver.

The sarsen stones are a siliceous form of sandstone called silcrete. Owing to the high composition of silica the stone is very hard. The name ‘sarsen’ is usually said to have been derived from the word ‘Saracen’, meaning foreign/alien (i.e. the Arabic/Muslim peoples mentioned in the crusades). I also came across a different origin relating to the Anglo-Saxon word ‘sar stan’ or ‘sten’ which translates as ‘troublesome stone’. Another more contemporary name for sarsen stones is Grey wethers, (relating to the stones likeness from a distance to grazing sheep). The sarsen stone was created 30-40 million years ago, when this area was said to be a tropical wetland ecosystem. Sand and silica mixed under these water habitats and over time, cemented & solidified. Some sarsen stones still have the holes remaining where tree roots and trunks grew within the sands. This layer of sarsen stone was broken up around the last ice age and deposited predominantly within the valley areas by glaciation. These deposits being specifically known as sarsen drifts. This process, as well as heavy melt waters, finally created the landscape we see today.

Personally, I have always found the stones owning a unique presence and awe within the landscape. Their feel, texture, patterns, the holes, the weathering, the lichen and the puddles, all owing to this uniqueness.

(At another nearby site, called Fyfield Down, the largest concentrations of sarsen stones in the

vicinity can be found. Having visited Fyfield Down on many occasions over the years, I never tire of walking in this somewhat other-worldly setting. So if there is anyone reading this that has yet to visit Fyfield Down National Nature Reserve, then I highly recommend it. A spring visit will see lots of bright yellow gorse out in flower. The smell of these flowers, is to me, reminiscent of coconuts).

Lockeridge Dene is also an important chalk grassland site with examples of many chalk grass related animal and plant species. The site lies on a south/south-east facing chalk hillside and can be a warm sight during the summer months. This warmth is loved by the Yellow Meadow Ant and much of the hillside is scattered with ant hill colonies. Whilst standing on the slope, we heard a brief talk about the chalk grassland ecology and talked about the flowers and butterflies seen here. We then talked about the lichen communities that are found on the sarsen stone. One particularly rare species being only found on this type of stone. I enjoyed photographing these sarsen stones decorated with colonies of lichen. Each stone has a unique pattern and composition of species.

On the sunny walk back through the valley, I noticed and snapped this cheeky blue tit eyeing me from a bush.

On the sunny walk back through the valley, I noticed and snapped this cheeky blue tit eyeing me from a bush.

We ended the session back at the Ed. room for a chat and some lunch. One member had brought back some tree lichen for us all to look at. They had also brought with them a nifty little hand lens so we could all see the lichen and stone examples up close and personal. Very cool!

I must say the project is something I look forward to every week. It is a nice place to meet interesting people, with the added bonus of lots of fresh air, scenery, history and nature. There are good conversations to be had and, of course, there is always something new to learn. Being involved with the project gives a sense of purpose, an act of doing and achieving. Granted, it may involve many great challenges, however, there is a huge potential of satisfaction waiting to be gained from it.

Next Week: The Sanctuary & Ridgeway Barrows.

On the sunny walk back through the valley, I noticed and snapped this cheeky blue tit eyeing me from a bush.

On the sunny walk back through the valley, I noticed and snapped this cheeky blue tit eyeing me from a bush.

Emerging out of the barrow and back into the world of the living, we were greeted by sunlight and the song of skylarks. We all got into a line for a group photo along the stone façade and then preceded to sing the Human Henge classic, “piggy pig, dog dog”. We followed some steps up to the top of the barrow mound and walked its length. From here great views were had. We came around the flank of the barrow chatting as we walked. One group member noted how the meeting of people on this project really brings her out of herself. It is a way of escaping other things going on.

Emerging out of the barrow and back into the world of the living, we were greeted by sunlight and the song of skylarks. We all got into a line for a group photo along the stone façade and then preceded to sing the Human Henge classic, “piggy pig, dog dog”. We followed some steps up to the top of the barrow mound and walked its length. From here great views were had. We came around the flank of the barrow chatting as we walked. One group member noted how the meeting of people on this project really brings her out of herself. It is a way of escaping other things going on.